Record date:

Francis Anderson Transcription.pdf

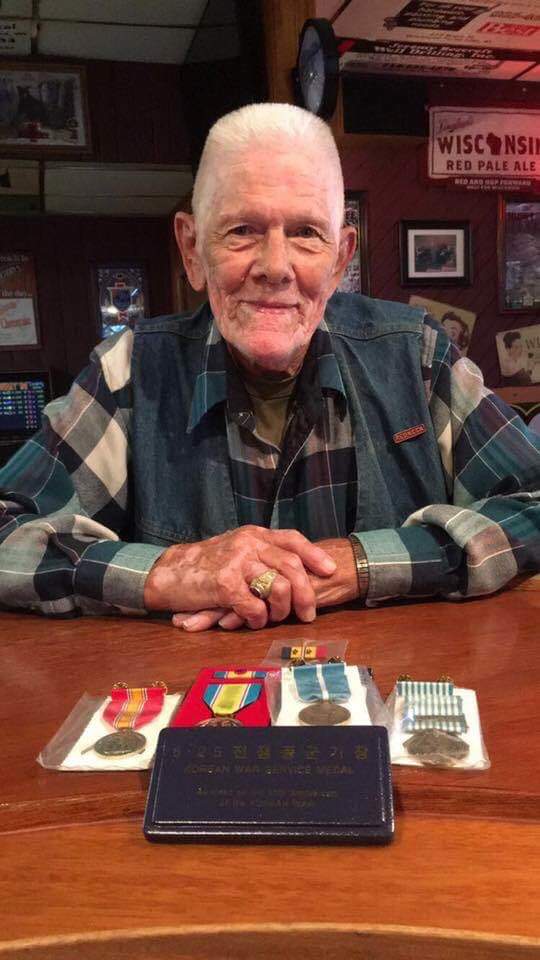

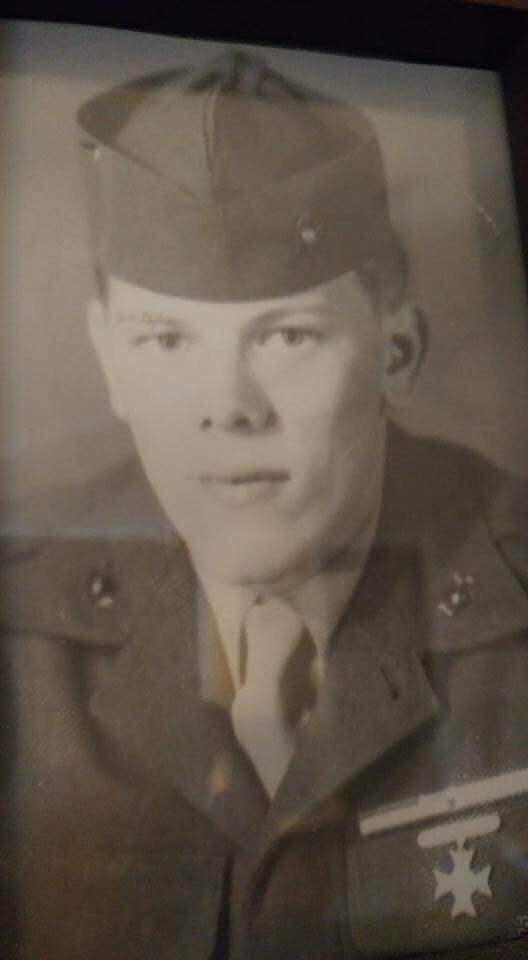

Sergeant Francis “Swede” Anderson VMO 6, Marine Observation Squadron 6, 1st Marine Division Air

As part of the VMO 6, Sergeant Francis Anderson flew on pioneering helicopter missions of reconnaissance and medical evacuation, during “The First Helicopter War”. As stated by Brigadier General Edward A. Craig, “Without them I do not believe we would have had the success we did [in Korea]”

Born in a farm in Wisconsin in 1930, Francis Anderson moved to the nearby Turtle Lake, a railroad town of about 1000 people, as a teenager when his mother found employment there. It was there where he chose to live his whole life, outside of his military service, until his passing in 2018.

News was obtained through battery radio – as there was not electricity on the farm, in in 1941 – and Korea was, at best, mentioned briefly, in school textbooks.

Although dubious about the prospect of being drafted to the Marines, rather than Army - his friend volunteered the two of them at the Minneapolis induction center - Anderson was ultimately grateful for the excellent training.

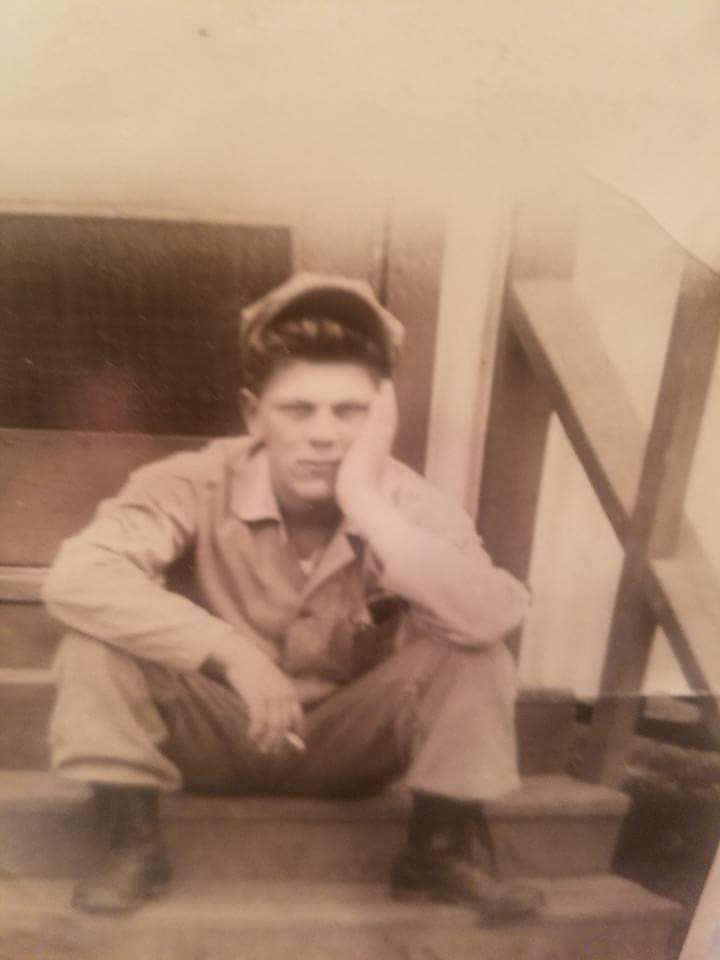

Basic training at Camp Pendleton, California, for a sixteen weeks, in 1951, was run by crusty combat veterans of WWII, such as his Senior DI [Drill Instructor] Sergeant Hodge, “… toughest guy I ever saw … knife scars and bayonet scars on his neck and face”. In addition to physical fitness training, instruction on using a M1 (“a far cry” from a hunting rifle), inductees seemed to be being intentionally ticked off by their superiors. Anderson’s platoon was also a testimony to the beginnings of President Truman’s Executive Order 9981, integration of services, in that there were three non-Whites in his platoon.

Without further ado (or training), Anderson was rotated to the 24th Replacement Draft, namely a twelve month tour in Korea. He describes his difficult voyage, though a hurricane on the USS General William Weigel, “If you think a hangover is bad that's nothing compared to sea sick.”

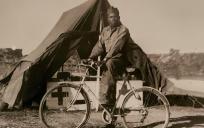

Anderson provides a fascinating description of the US military’s newly adopted Bell helicopter and his role in reconnaissance and rescue. After a ten day indoctrination to mapping, an exchange of his M1 rifle to a M1 carbine which could fit into the helicopter, he was good to go.

The two seated, open, bubble helicopter powered by a small, single engine, would typically fly through canyons where there was a concentration of Korean troops in caves, using a narrow-gauge railroad tracks to roll out weapons and to fire rounds of artillery. Anderson would identify the grid numbers and azimuth on the map while the pilot would immediately communicate with the fighter planes behind them, via radio.

Although a native of northern Wisconsin, the cold of Korea’s 38th parallel was unequalled. Luckily, the servicemen were issued heavily insulated boots, clumsy, but prevented frostbite. During the winter, a door was put on the Bell and the engine which was behind the cab provided some heat.

Anderson explains that, unfortunately, medical evacuees were subject to frostbite. The helicopter had a conduit frame so that a stretcher, placed within a basket, was strapped down to each of the skids. In some cases, the legs of the wounded were sticking out. A mechanic improvised a hood of sheet metal that snapped on top of the basket but some cold air came from the bottom, worsened by the propeller’s backwash.

In 1953, Anderson got his sergeant stripes on his pleasant voyage home aboard the fittingly named USS General A.E. Anderson, a clean troop ship where he enjoyed good food and good weather.

This interview provides a vivid snapshot of what is often called America’s Forgotten War.