Record date:

Melvin Cohen - Technician

From Radio Operator and Repair School to Calvary horses to burial detail, Cohen was undeterred by whatever challenge the US Army threw his way during World War II and beyond.

Born in 1926, Melvin Cohen grew up under the tough circumstances of the Depression in the West Side of Chicago. Melvin and his sister, Helen grew up in foster homes due to their mother’s trauma having been stranded in Europe as a result of World War I and the Russian Revolution. Melvin remained close to his parents, nonetheless. It was he who visited his father regularly in the hospital until his untimely passing and he fondly recalls apple strudels that his mother sent to him in the Army.

In spite of working three jobs to help support his father, Melvin graduated among the top twenty-five students out of three hundred, and in July 1944, he reported to the US Army. After a brief stay in Fort Sheridan, he was sent to Fort Riley, Kansas for basic training. He recalls learning the 10 general orders, firing an M-1 rifle, and the rile at indignation at being woken up in the middle of the night for KP.

After having taken aptitude tests, Melvin trained as a Radio Operator and Repair School, there. The radios, placed in M-8 armored vehicles, were vital tools of communication both for regular voice and for Morse Code. Cohen received the highest grade ever and he was then appointed as an instructor.

In spite of Cohen’s competence and vigorous searches for a radio assignment after that, he never worked in this capacity. He attributes this to unspoken antisemitism though he did not confront any overt antisemitism throughout his service.

Being at Fort Riley, home of the Cavalry had its advantages. Although horses were phased out and replaced by armored vehicles officers were still looking for equine volunteers. Cohen followed up and enjoyed horseback riding, so much that he later would introduce his children to this activity. He also met Lou Jenkins, the lightweight boxing champion, who gave him a few lessons in boxing. Next Cohen was sent to Fort Ord, California, to be shipped to the Philippines. The boat, SS Meridian, a captured German freighter was not ideal but he did not suffer any seasickness. He had a chance to apply his newly acquired boxing skills on board but found that one fight sufficed!

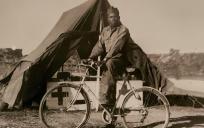

When the ship landed in Luzon in the Philippines, he was assigned to the 302nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, Mechanized, 1st Division, and given new equipment and clothing in preparation for the planned land invasion of Japan. Since the war in the Philippines was just about over, Cohen and his troops were responsible for “cleaning up” secured areas such as shooting flamethrowers in caves where the Japanese would be hiding. They were also responsible for finding dead American soldiers and burying them in identified graves. Cohen witnessed dead bodies upon which the Japanese committed atrocities, so shocking that he did not disclose them in his interview.

Luckily for Cohen, the land invasion of Japan was called off so he and his troops entered Japan as part of the Army of Occupation, instead. They were based in Camp Drake, about five miles outside of Tokyo, which had been a former Japanese army base. It was there where he found Japanese swords and rifles which he sent to his sister in the United States to hold for him. Cohen saw the Japanese signing the surrender of the USS Missouri and heard McArthur’s speech. Cohen was impressed by the average Japanese person’s linguistic ability, to speak English fluently. He also made it a point to ask Japanese soldiers about the shocking atrocities. Yet, he empathized with their response: they would have been shot had they done otherwise.

After fourteen months, Cohen was sent back to the United States, this time, he was on a US Navy Transport ship, which felt like a cruise liner. When the ship passed the Golden Gate Bridge, Cohen choked up, remembering how when he left he wondered if he would return and see it again. When they landed at Angel Island, they were treated to steaks, served by POWs from the Afrika Korps who were eager to stay in the US and become citizens.

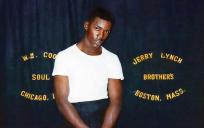

Since Cohen wished to derive the maximum benefit from the GI Bill, he needed to re-enlist for one year. After a two-month furlough at home, he was assigned to the 87th Battalion of the 2nd Armored Division, at Fort Hood, working as a clerk. He also taught himself to drive a large truck to pick up and deliver requisitioned supplies. A favorite pastime was playing football as part of the 1st Cavalry Team. Indeed the photo below was taken when their team won the game against the 11th Airborne Division. Cohen in the position of fullback scored two touchdowns then.

After his discharge, he studied accounting at the University of Illinois at Champaign, wanting to be among his friends who studied there, too. He relinquished his original ambition of architecture so that he could be financially stable as quickly as possible, marry and raise a family.

He met his wife at a dance at the Drake Synagogue in Albany Park. The couple had four children and he feels fortunate to have shared sixty-four years together.

Cohen suffered hearing loss and tinnitus as a result of rifle range practice without ear protection. He is grateful for the VA coverage of the costs of hearing aids. His best friend, Jerry, stepped on a mine and his leg was amputated below the knee. While most of Cohen’s friends’ were discharged from service unscathed, many passed away under the age of fifty, nonetheless.

Not one to philosophize, Cohen has a down-to-earth understanding of his military service.

“People used to ask me, "When you were in the war, were you afraid?" And I would say, "Of course… Nobody wants to die. That doesn't mean that you shirk your duties.”