Record date:

Elihu Carranza, Sergeant, Marine Corps

“I was able to think my visual thinking about the landscape, about others, about threat…I was born with [it] and was really a gift… but a gift that had a sense of responsibility built into it.” Thus, recounts Elihu Carranza in the context of a section leader, driver, and .50 caliber gun operator of the 1st Platoon, 1st Section of the 7th Transportation C Company in the Vietnam War. Visual thinking as well as memory and its reconstitution following PTSD, re-learning of lost language skills, documentation of specific events, assistance to veterans as an outcome of duty, and the seeking of a higher morality, are discussed in his interview.

Born in 1947, Mr. Carranza largely grew up in San Jose, California where his grandfather had established the first Hispanic Baptist Church, emphasizing social justice and education. His father had a military career as a fighter jet pilot and later as a professor of Logic, Speech, and Communication. His mother who hailed from New Mexico has American Indian and Mexican roots. Generations of his family worked on farms, and Elihu recounts the picking fruit in the orchards of the Santa Clara Valley in California. Having an innate sense of the visual aspect of life on farms, as well as having been well-traveled as a child of an Air Force family is the backdrop for Elihu’s quotation above. As a teenager, he chafed against the stereotypical expectation of going to trade school, the direction perceived to be suitable to Hispanics, at the time. After numerous episodes of missing school, the juvenile detention offered a choice of military enlistment. Thus seventeen-year-old Elihu enlisted in the US Marine Corps in 1965, in the aftermath of a four-month probation period.

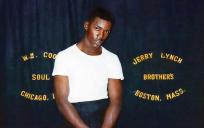

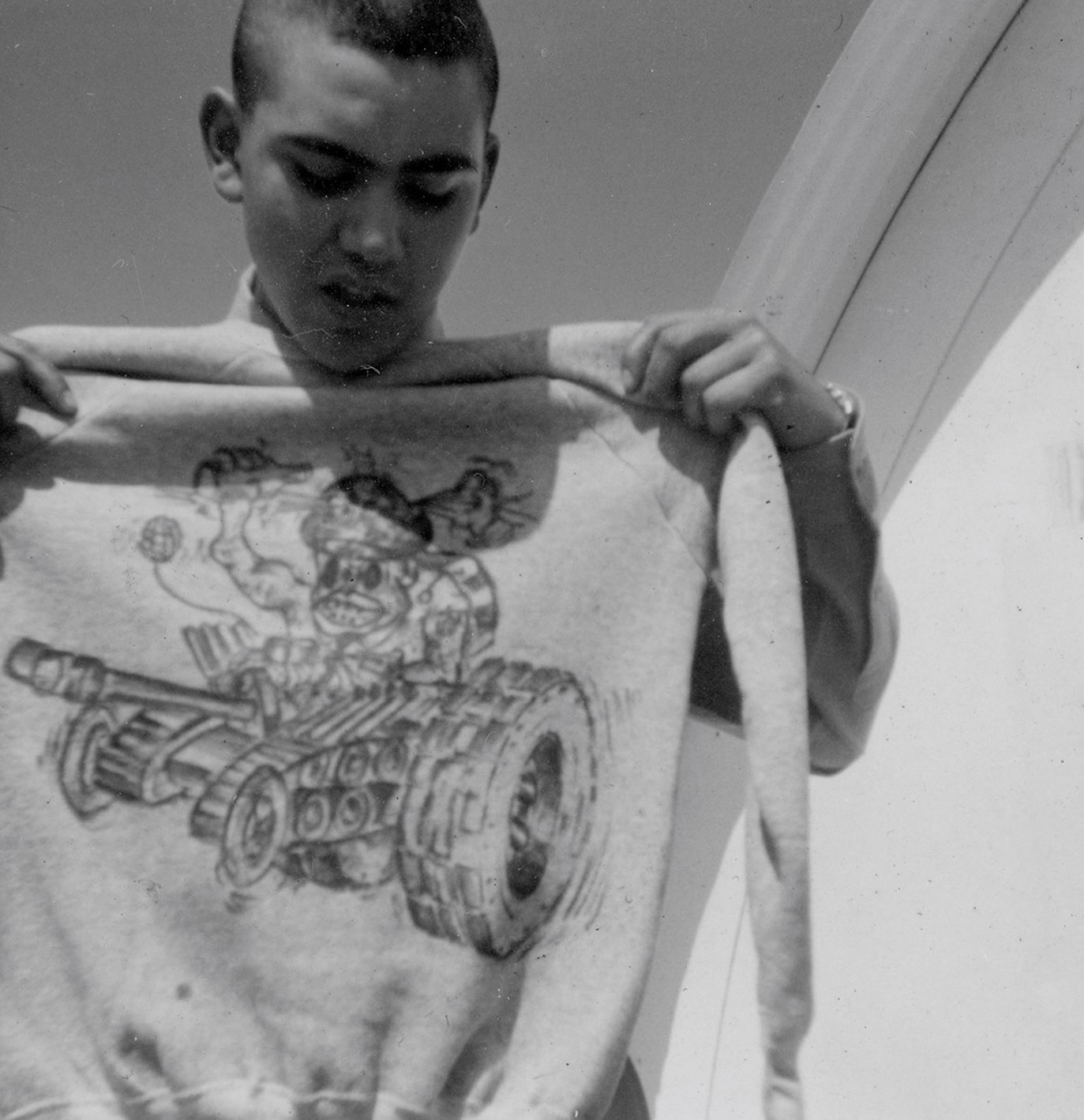

Elihu trained at Camp Pendleton, California. Soldiers there would ask him to draw his cartoon logos on their sweatshirts. Given his visual acuity, Elihu was disappointed to find himself serving in the 7th Motor Transportation Company, rather than fulfilling the expectation as a combat artist. He nonetheless strove toward excellence of the rank, itself, striving being a constant of his constitution. At times, however, he became an object of envy for his leadership roles.

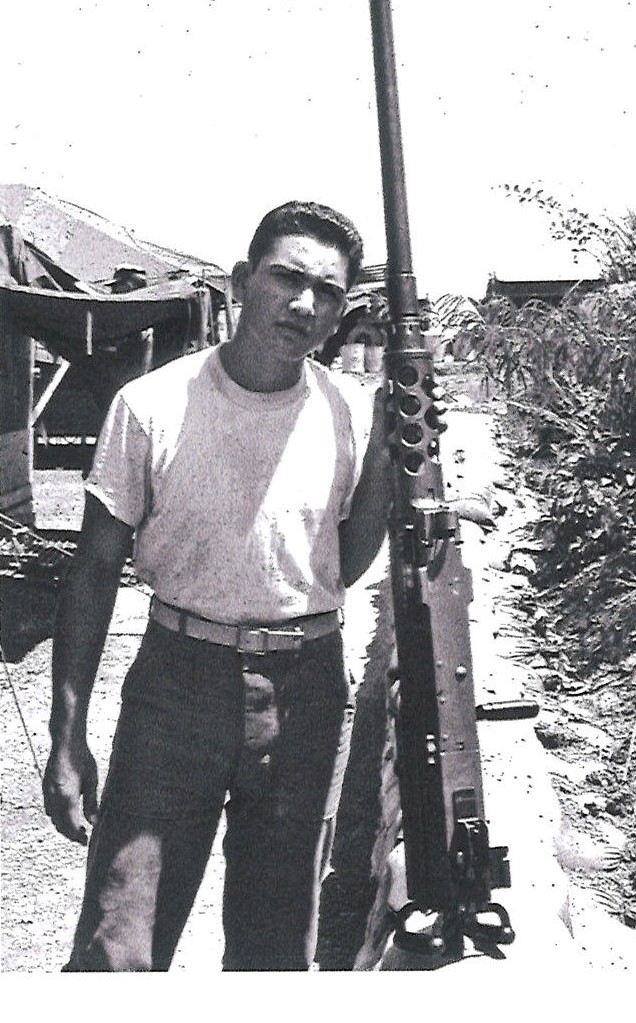

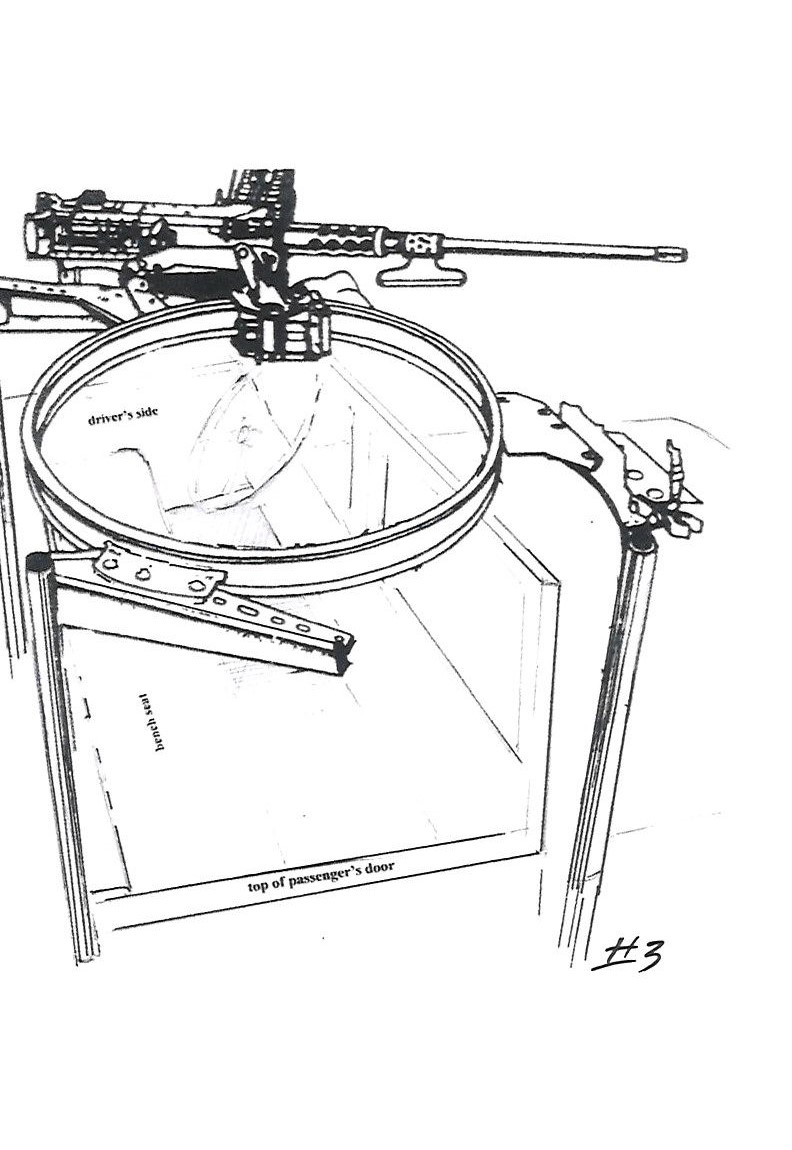

In 1966, his transpiration battalion arrived in Chu Lai, and his company was deployed for Operation Utah where North Vietnam troops engaged the American military. His unit served throughout the I Corps Region, from below Chu Lai to the east of Highway 8, below the DMZ [demilitarized zone]. In addition to his duty as a driver and section head, he also operated the vehicle’s .50 caliber gun, mounted on a military truck. He recalls exercising restraint in using the .50 caliber gun; feeling that the fire power was excessive and often a result of panic.

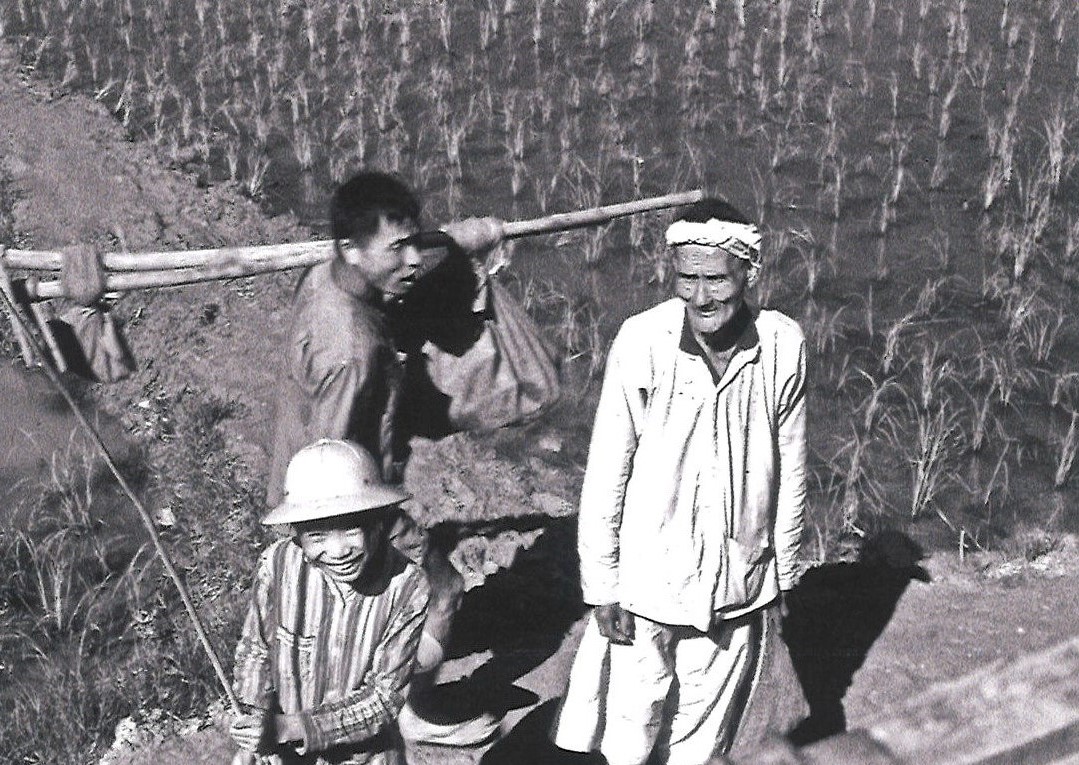

His photographs of Vietnam reflect his position in the vehicle while traveling on and off roads, from village to village, from one hill camp to another hill outpost. Mr. Carranza presents a grim reminder of many unnecessary heroics. For example, Captain Bradley, likely at the behest of gung-ho Marines under his command, sent the men to go beyond their transportation duties on patrols and operations. Motor transportation, Elihu believes, was viewed as inferior to operational military duty. On the contrary, he testifies that the convoys of trucks were frequently under fire. Carranza himself had three near misses from sniper fire. During a trip from Chu Lai to Da Nang, he experienced the aftershock and blast of A-4 passing to his right hand and his head. He suffered a concussion from the incident. His unit transported a range of items used by the US military including empty containers of Agent Orange and other chemicals. Also, although the US policy was not to supply South Korean troops in Vietnam, Elihu recalls a transport to a South Korean ship to a remote area in the I Corps Region. Four trucks were sent for the delivery, and his own return to his unit was fraught with uncertainty. Mr. Carranza documents the conveying of prisoners of war, from field pens to prison camps. Driving meant traveling off roads in heavy mud into remote and usually dangerous areas. After six months, the soldiers in his unit were reassigned. He regrets the loss of being part of a cohesive group with whom he trained and traveled.

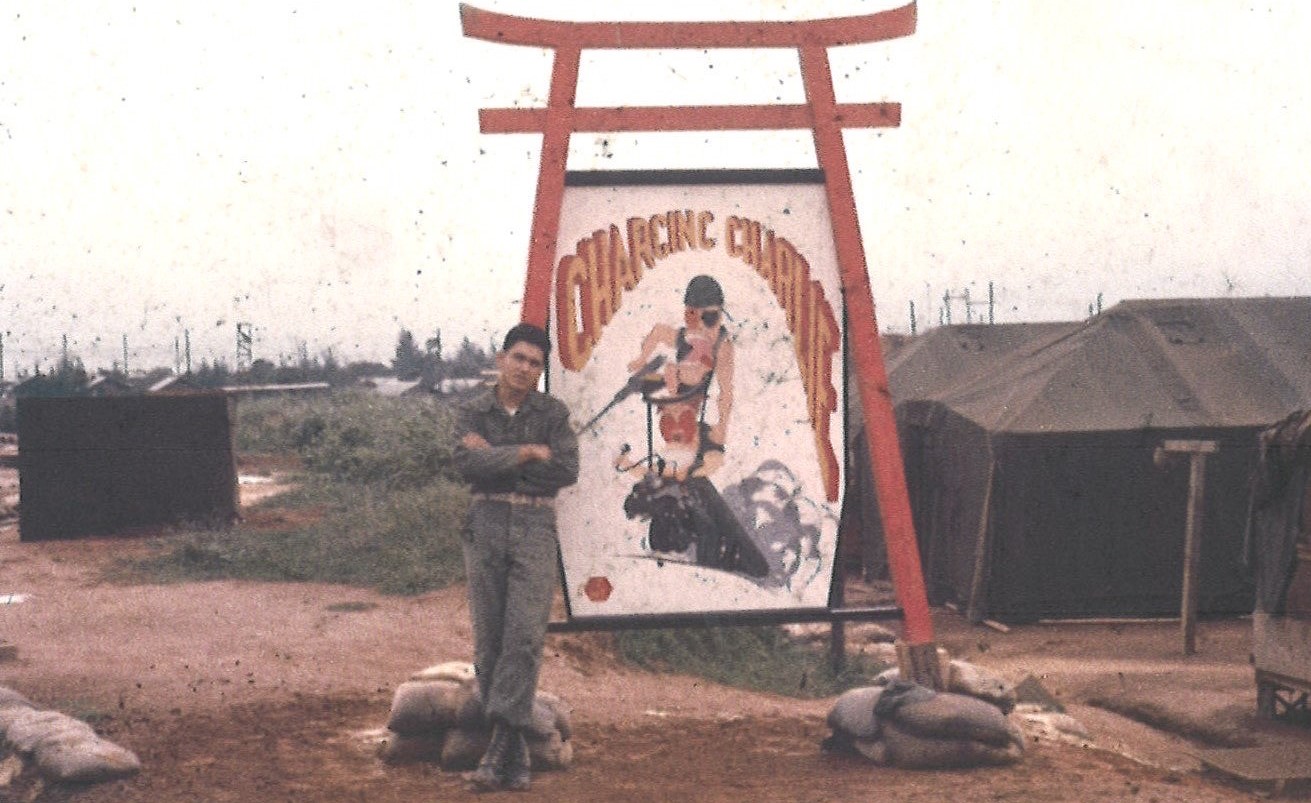

Elihu took photographs of the travels throughout the I Corps Region. With a Petri 35mm camera in his hand he would randomly shoot photographs sometimes by simply reaching out from the ring mount. One of the photographs documents the location where his head was nearly shattered by a bullet. This shooting was immediately followed by another round from the sniper hidden in the lower side of the mountain. Mr. Carranza identified with the villagers, as he does now, having grown up with fields. He would draw the Vietnamese workers in various situations, using pencil, or ink. Some of his drawings and photos are shown below. One photo is that of the company sign, which reads “Charging Charlie” that Mr. Carranza designed and built. The cartoon is indicative of war and transportation duties.

One year later in 1967, his tour of duty ended, and he was then assigned to Special Forces Transportation Operation at Camp Geiger, the Marine Corps section of Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. There he rose to the rank of sergeant. Many men under his command had returned from their tour of duty with the Transportation Battalion in Vietnam. Carranza understood that their oppositional or unusual behavior was not a reflection of bad will but rather the result of trauma, what is understood today as PTSD. Mr. Carranza, too, was not free from suffering due to PTSD, fatigue, and perhaps from his concussion. This was manifested in disjointed writing and speech. In order to overcome his language impediments, he took courses and retrained himself to read and write. Elihu was discharged from the US Marine Corps in 1969. He graduated with an undergraduate degree from Stanford University of Palo Alto in 1973. He continued his education and, in 1978, he graduated with a Masters of Fine Arts in Painting and Sculpture with Honors from Columbia University of New York City. About a decade later, in, 1989, he added another degree by graduating with a Masters in Biblical Studies from Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia.

Today he and his wife Susan both work as artists in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, and their son manages his company of higher computer technologies. He is grateful to Amy Mondt of Texas Tech University who located documents to assist with veteran research. Elihu’s photographs of Vietnam and his military archives are at the Vietnam Center and The Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive there. His art and poetry represent a life-long struggle with PTSD - a triumph in a war that was lost.