Record date:

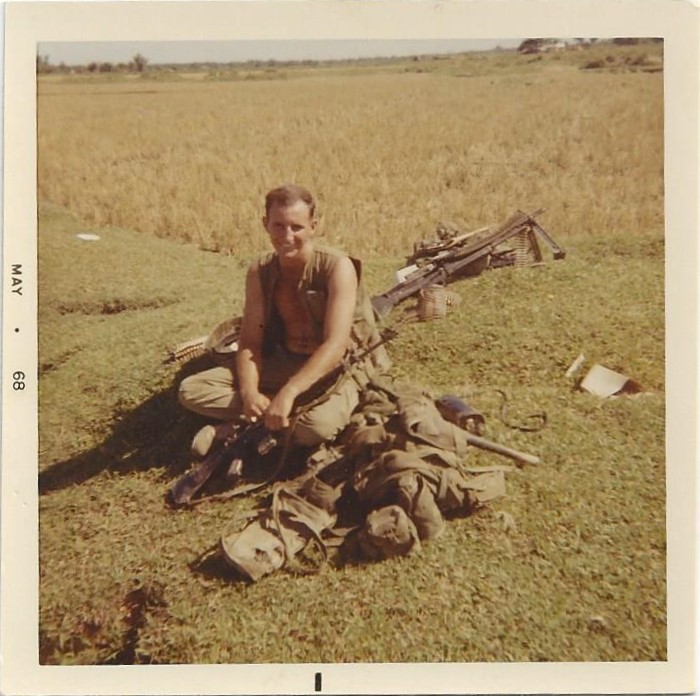

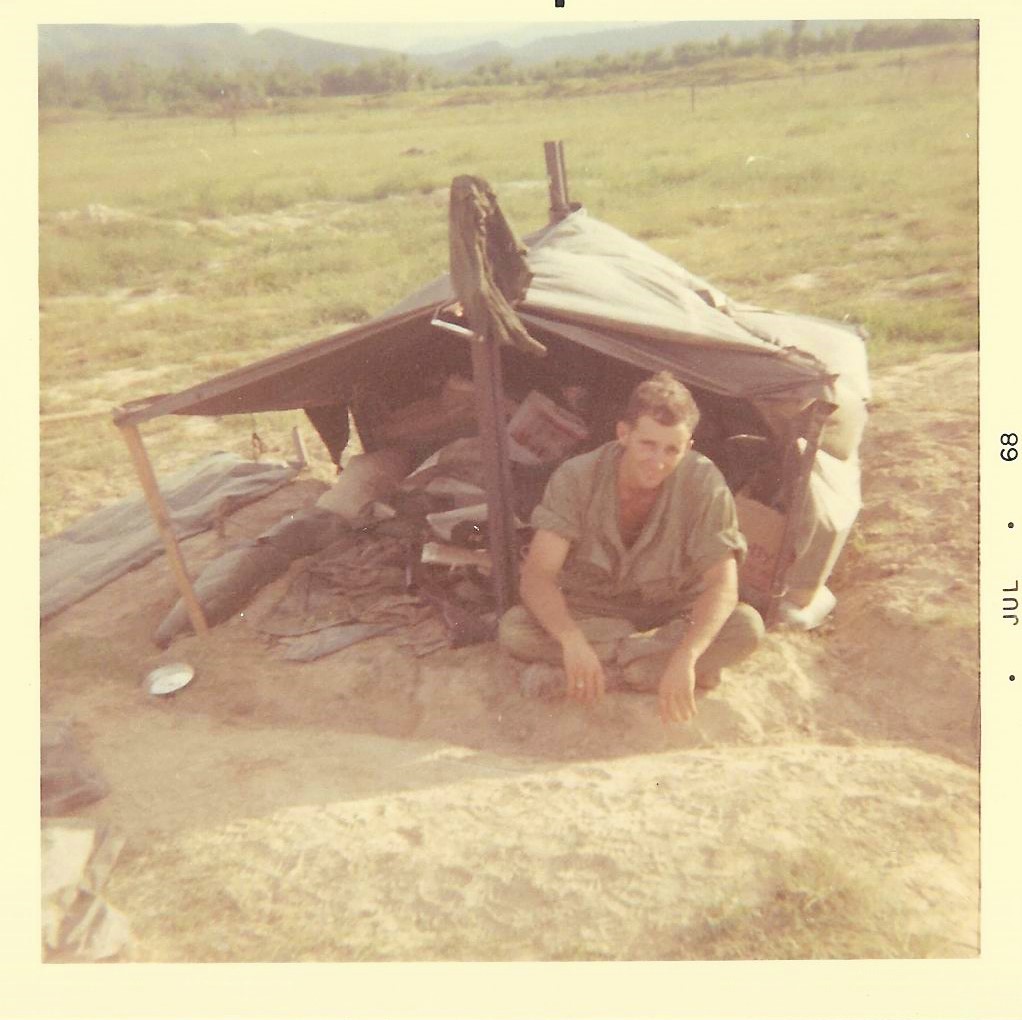

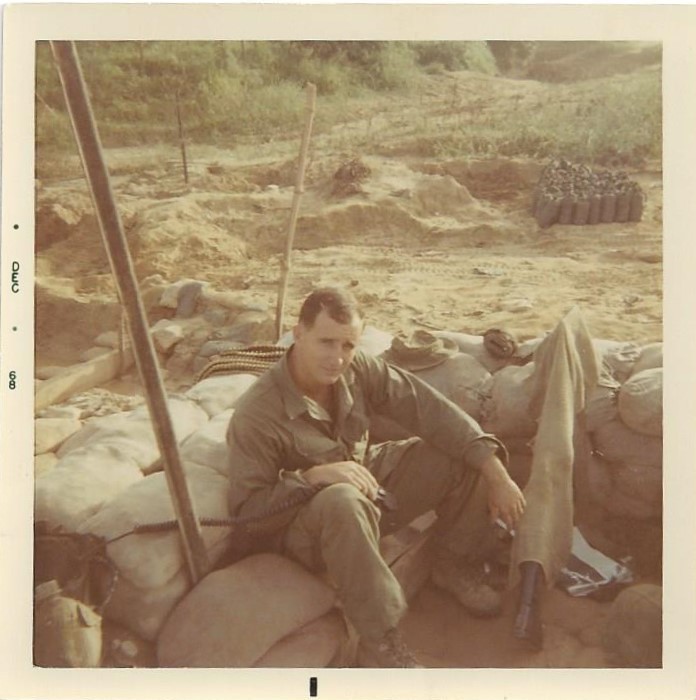

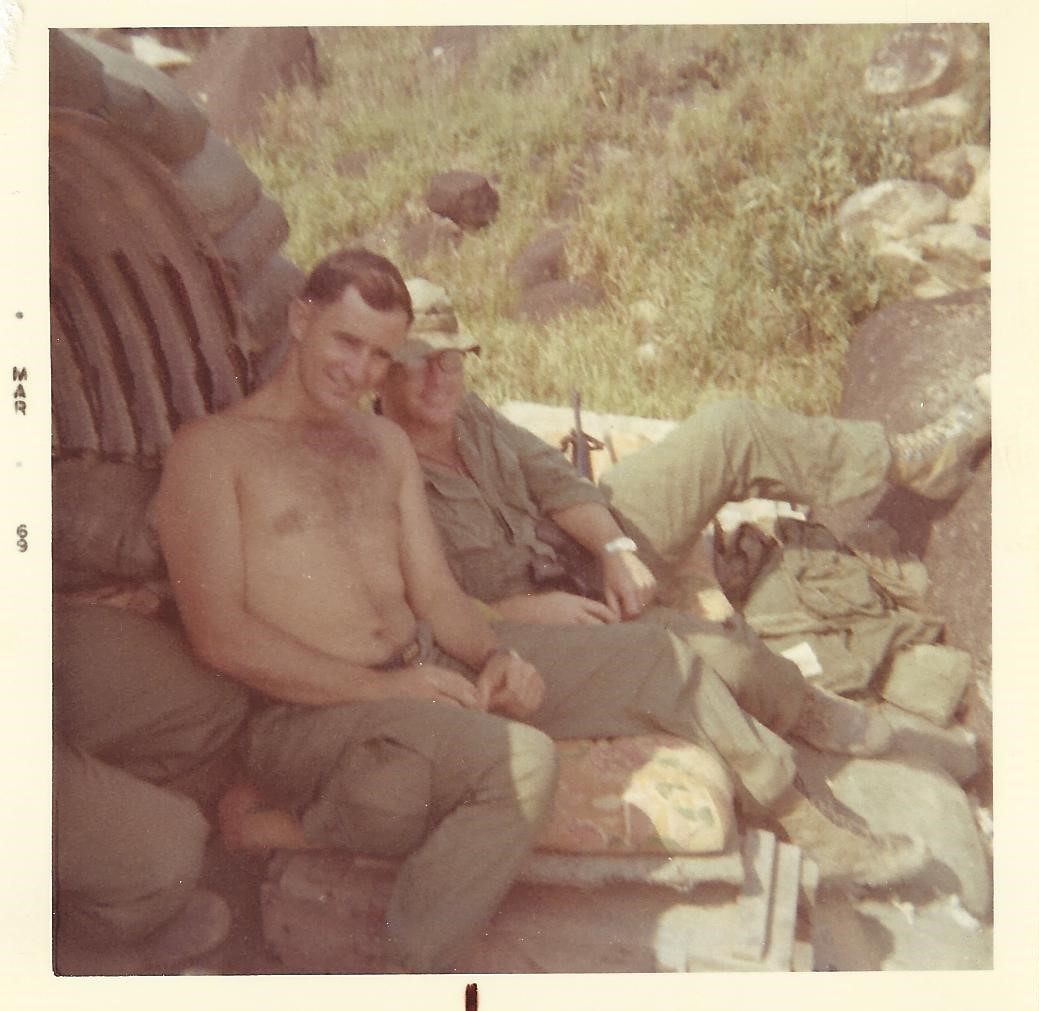

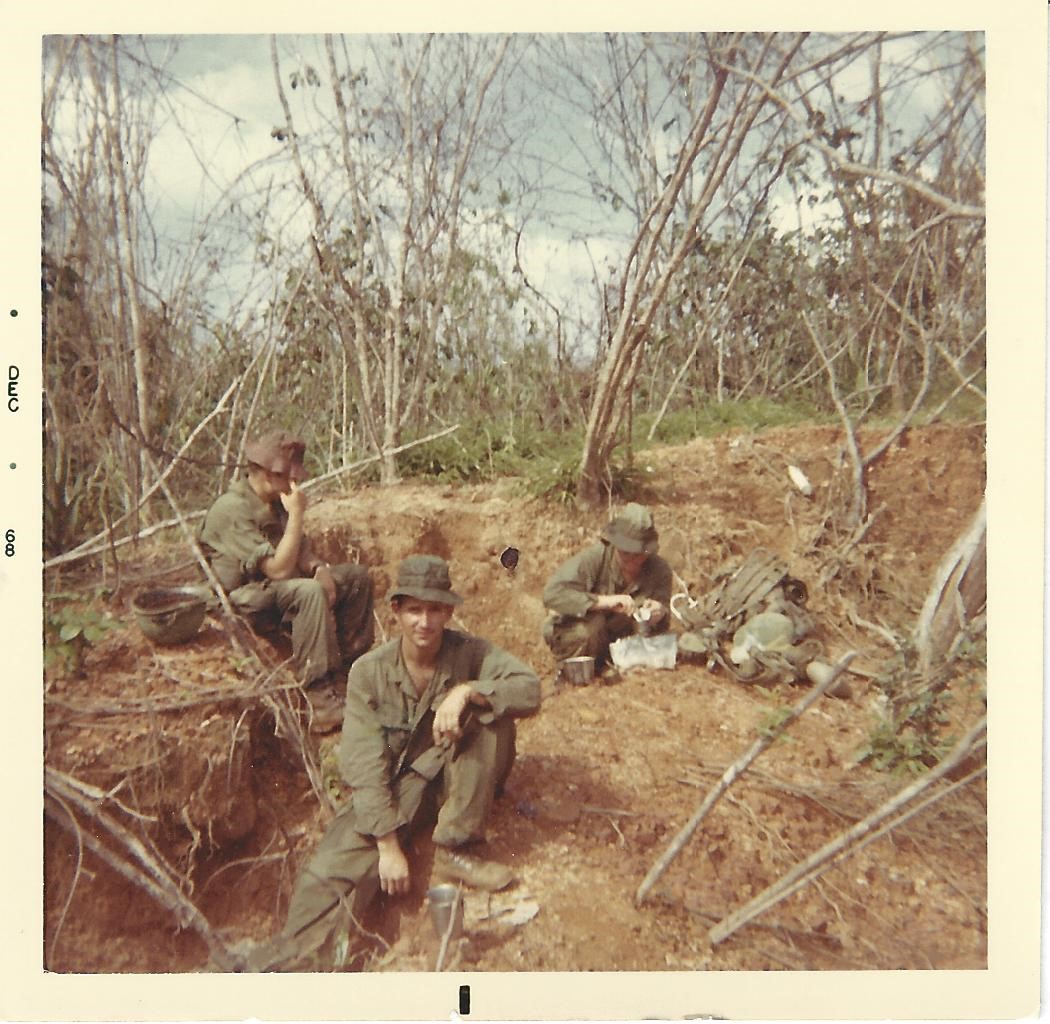

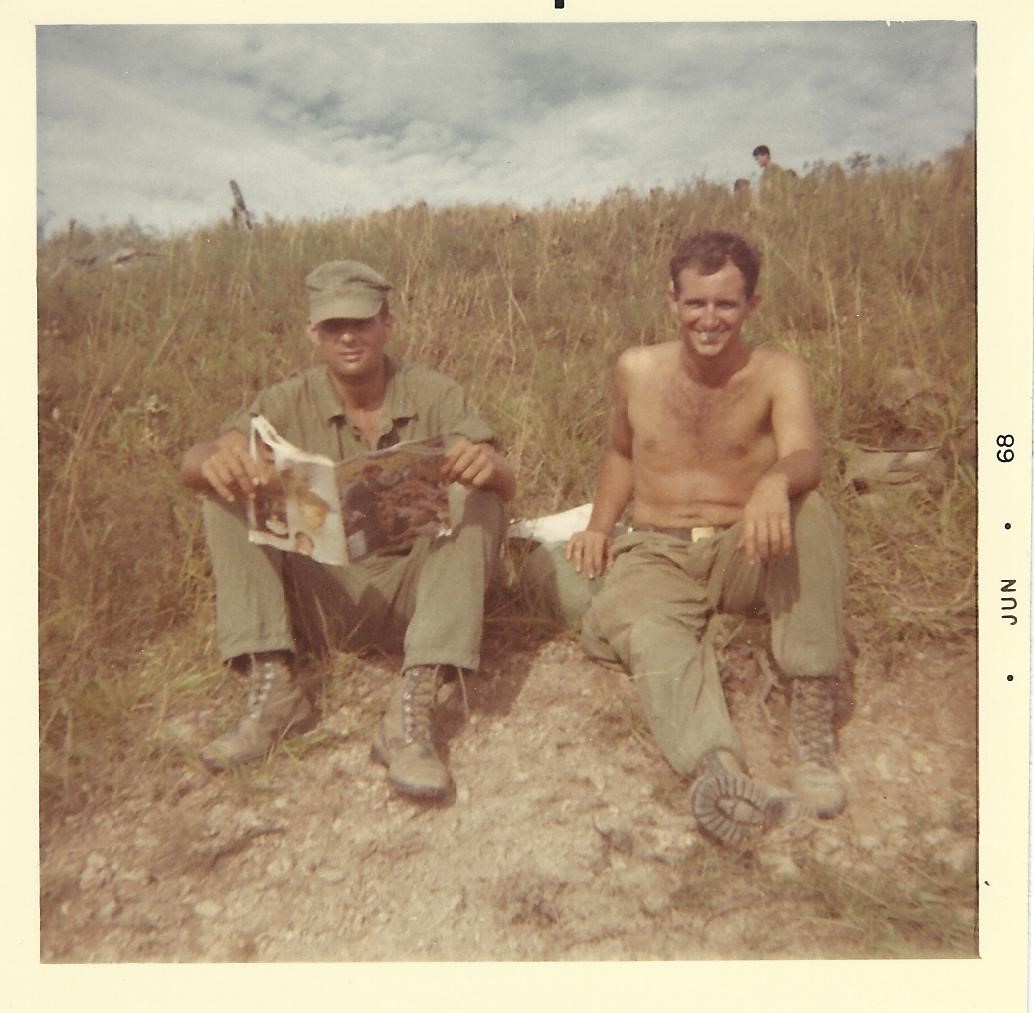

Harold Hoss, SGT, 101st Airborne

The Vietnam War is one of the longest and bloodiest wars in American history, and no division’s combat record during the war can match the 101st Airborne’s. Harold Hoss saw this first hand as machine gunner in the unit.

Born in Dodge City, Kansas, Hoss was the eldest of eight children—five boys and three girls—and grew up on his father’s farm. His father and uncle both served in the military during World War II in different theaters, the Pacific and Europe, respectively. Hoss enjoyed helping his father on the farm and after graduating high school, he attended a trade school for farm mechanics to stay clear of the draft. After he completed the two-year education program, he worked as a mechanic in a farming machinery dealer. It was brief, though, because he was called up for military service. “That put me right in… about the worst time I think,” he laughs.

Hoss had his basic training in Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri and the tough training was too much to handle for a few recruits. That wasn’t taken lightly by some non-commissioned officers, who were busted for blanket parties, where they’d throw a blanket over a recruit and beat them. After Fort Leonard Wood, Hoss went to Fort Polk, Louisiana, for advanced infantry training. While the training was even tougher; remarking that the officers mentally prepared them for war. “[They’d] knock you down physically and get you back up to where you’re confident enough to be a good soldier,” he says.

Afterwards, Hoss was sent to Vietnam and assigned to the 101st Airborne Division on March 7, the same day as his interview with the Pritzker Military Museum & Library. “Fifty years ago today,” he laughs.

As a member or an airborne unit, spending the night at a base or in a single location for long was a rare event. They’d move frequently to different places with various terrains: flatland, jungle, and mountain. His platoon was tasked with running patrols to clear the area of Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, guarding bridges, and setting up ambushes. Missions would last weeks, and a firefight was never far from Hoss. Some missions had nonstop contact with enemy forces for more than two weeks.

Hoss’ unit also fell into heavy fighting in the A Shau Valley. During one firefight, a soldier pulled the pin off a grenade but dropped it in front of him. “Get down! Grenade!” Hoss hollered. Thankfully, there was a crater next to the soldier, he jumped in, and nobody was hurt.

During his tenure in Vietnam, casualties were high, both from hits from enemy and sometimes as a result of friendly fire. One night while Hoss’ squad was guarding a perimeter, an instant NCO got up to use the restroom. He stepped outside the perimeter, though, and another soldier mistook him for an NVA troop and shot a three-round burst from his M16 rifle. One bullet hit his arm, the second hit his shoulder, and the third hit a Claymore mine next to his head. To the NCO’s luck, the mine was damaged and didn’t go off, and he was sent home.

With the torment of war and the fear from the killing and high casualties, some men opted to shoot themselves in order to go home. One soldier in Hoss’ unit shot himself in the foot while they were on a patrol. “We had to drag his ass out of there and haul him to where he could be choppered out,” he says.

Hoss returned home after a year in Vietnam, and says he was overcome with emotions when his father picked him up at the bus station. After reuniting with his family, Hoss told his brothers to study hard and stay in school to avoid the draft. None of his brothers served in the military. He later made good use of the GI Bill and enrolled at Emporia State University in Kansas, where he met his wife, and earned an elementary education degree. While he was still farming, he began teaching. Hoss enjoyed educating children, but after three years, he decided to commit solely to farming.

Serving in the military and fighting in a war such is Vietnam will change anyone, and Hoss is no exception. He is proud of his accomplishments and considers himself lucky to escape the deadly war unscathed. Despite learning and maturing from the experience, he wouldn’t want to go through it again, though. “I wouldn’t take a million dollars to do it again but am glad I did it and got through it,” he says.