Record date:

Meyer_Widrevitz Transcription.pdf

Meyer Widrevitz, Sergeant and Outspoken Patriot

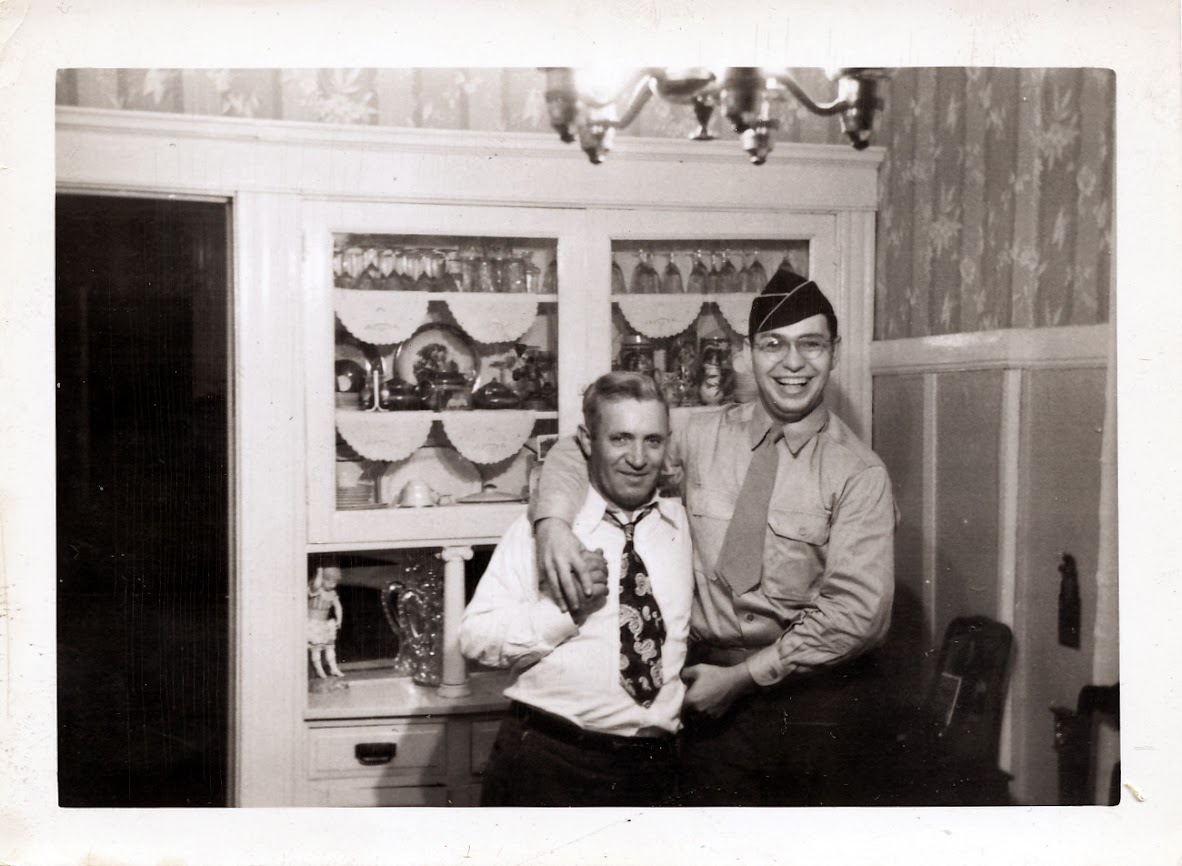

Meyer Widrevitz was born in 1920 to plucky, immigrant Jewish parents, who met as young adults in Chicago. Both had risen above obstacles such as the privation that forced them to work while still children. In time, his father opened a flooring store and the two raised Meyer and his sisters in Chicago’s West side, then home to Jews and numerous other immigrant groups.

The Widrevitz parents valued a religious Jewish education, in addition to the schooling at the public schools, but Meyer, as young teen, put a kibosh on that. Nonetheless, Widrevitz continued to believe in God and to identify staunchly as a Jew.

The intellectually inquisitive Meyer enjoyed his studies and in 1937, at the prompting of a friend, signed up for an adult education course on radio receiver and transmitter electronics. This happenstance was to have an impact during World War II, in that he was assigned to the Signal Corps.

Unlike most Americans who were shocked by the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Meyer was aware of the Nazi threat, by the late 1930s. Not only had he had participated in a propaganda analysis club, he also wrote letters requesting (and later receiving) news bulletins from Germany and other countries. He also encountered German Jewish refugees, sometimes in a pitiful state, when working in his father’s store.

Meyer learnt about the forthcoming Army Specialized Training Program [ASTP], when studying law at DePaul University. After half a year or so, in August, 1942, he enlisted to what became the first cohort of the program. The Army’s promises such his promotion to 2nd lieutenant never did materialize but Meyer did train for a few months at Chicago’s Armor Institute and at Philco.

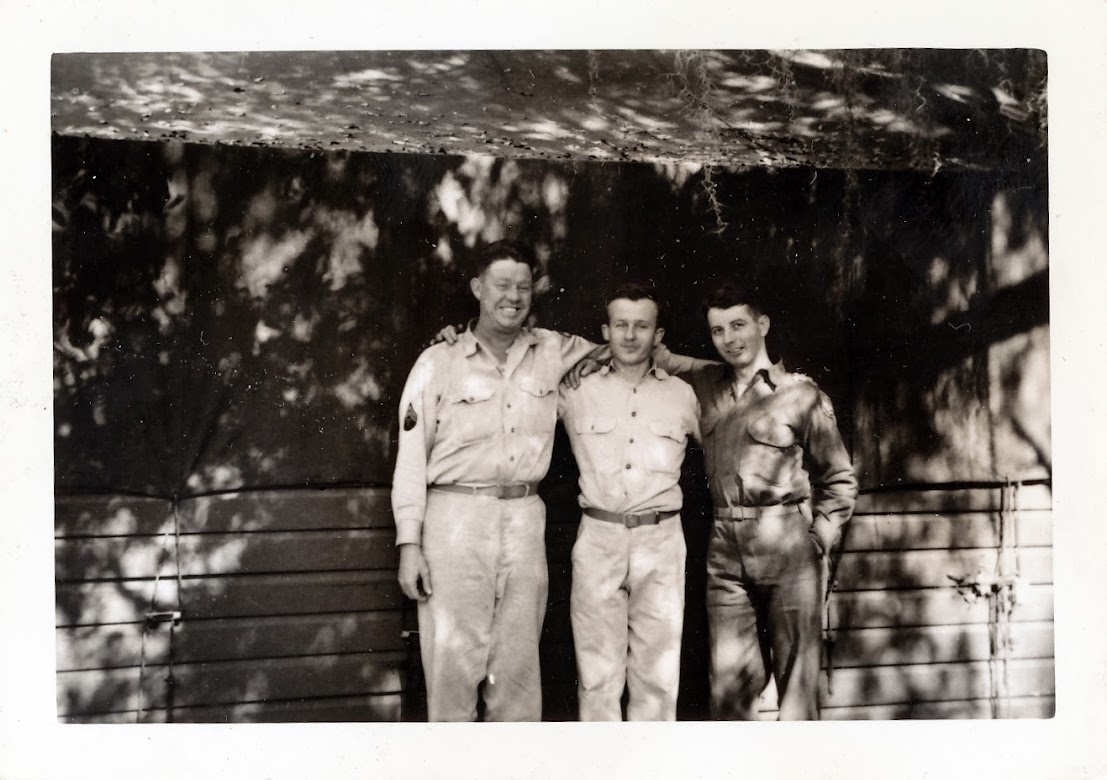

Widrevitz, assigned to the 26th Signal Platoon, in Florida fell thirty feet to the ground when climbing a ladder of logs in a training exercise. He wound up in the hospital semi paralyzed for a few weeks. In spite this and other health issues, Widrevitz, felt that it was his duty to serve his country. Still, he is not a blind patriot, and criticizes the US military’s lack of caution during training which caused unnecessary injury or death. For example, after having called for volunteers to stand in pits, the trainers explained, “We wanna prove to you fellas this if you dig a hole deep enough, that the tank will not kill you.”

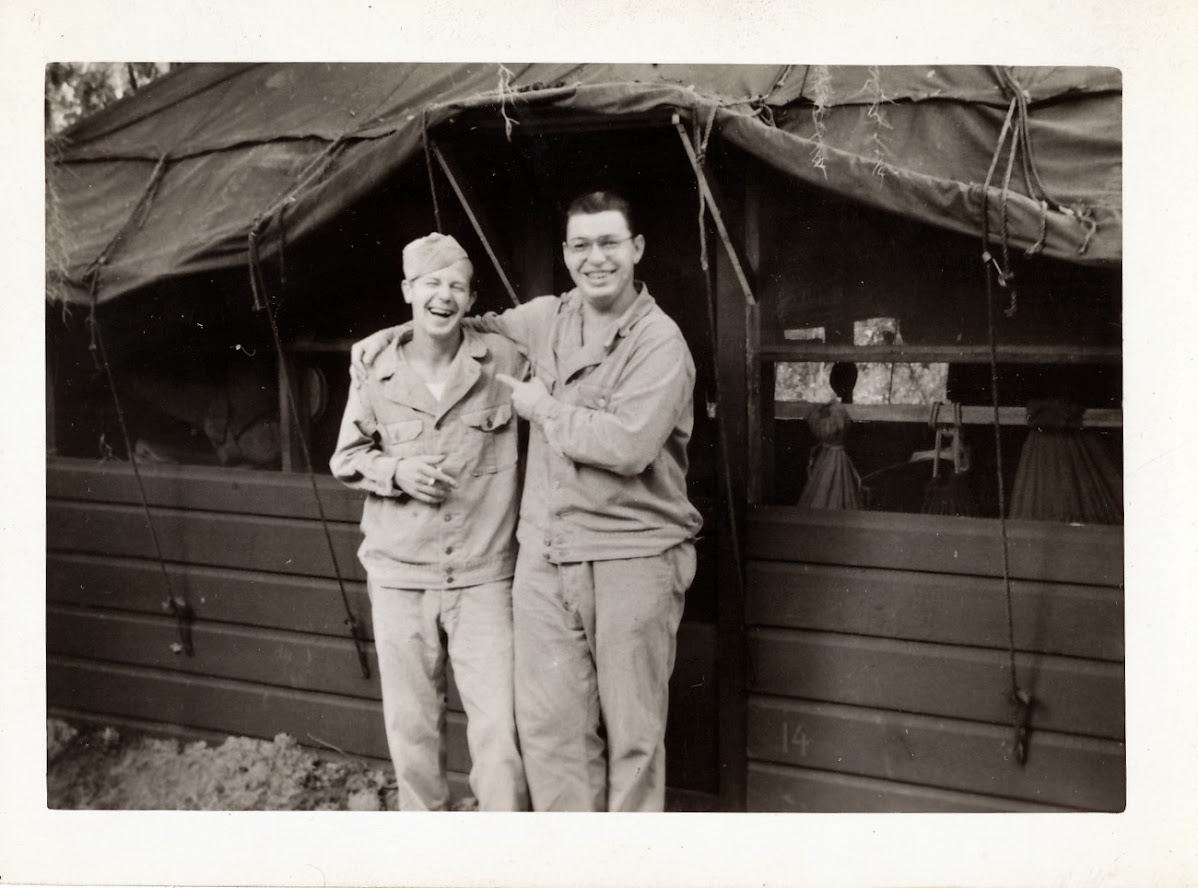

Not shy of confrontation, Meyer humorously recounts how he redressed wrongdoings especially when it came to inequitable distribution of food or beverages during the journeys to and from the Pacific or he recalls the less than humorous confrontation with a blatant anti-Semite in his platoon.

After zigzagging across the Pacific to avoid kamikaze attacks, Meyer aboard a former banana boat reached Saipan a couple of months after the US conquered it, in September, 1944. As part of the 73rd Bomb Wing of the 20th Army Air Force, Widrevitz’s role was to repair the communication systems in the B-29s which could require improvisation and risk. He describes how he reattached the antenna to the rudder of a B-29, twenty-seven feet up from the ground:

“… they had a ladder mounted on a little platform … and you can't touch the ladder to the rudder, and here I am hanging on with one hand here trying to tie up the antenna…”

Widrevitz is attuned to the absurdity of the fortunes of war. He mourns, for instance the death a Private Van Melsen, who kept pestering his superiors to join a B-29 post-war mission of dropping medicine and food supplies to POW’s; only to die when the aircraft crashed into a mountain.

After liberation, he describes the confusion of the US Army as to which island the troops should be located, who would return home and when. Widrevitz literally nearly missed the boat since he and a friend drove a jeep up the mountain rather than wait at the shore, as instructed. Meyer’s understanding of the duty of the citizen is practical: "If you haven’t forty nine cents for a stamp or envelope, a telephone call to your elected officials, expressing your opinions, can affect their decisions. It’s never too late to motivate other citizens."