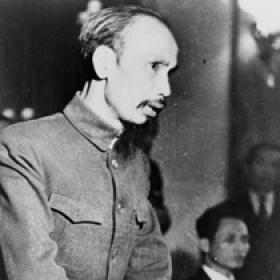

Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh (May 19, 1890 – September 2, 1969) was born Nguyễn Sinh Cung but was known in his youth as Nguyễn Tất Thành. During his youth, Thành studied in France, adopted a nationalist ideology rooted in Leninism, and worked in Moscow and China. In 1930, he founded the Indochina Communist Party. By the start of 1941, Thành had changed his name to Ho Chi Minh (meaning He Who Enlightens) and in May returned to Vietnam for the first time since 1911. Forming the League for Vietnamese Independence (Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng Minh Hội, known as the Viet Minh), he began fighting the Japanese occupation of Vietnam. In August 1945, the Japanese surrender provided the Viet Minh the opportunity to seize power in the city of Hanoi. On September 2, Ho declared the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. In December 1946, as the French moved to reassert control over their colonial empire, conflict with the Viet Minh broke out. After the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, the 1954 Geneva Accords granted independence to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, though the latter was split into two nations: a communist north and a democratic South. Ho oversaw the enactment of land reform and the consolidation of communist rule in the North in a bloody campaign. All the while, communist forces in the South were organized against the democratic leadership in Saigon. In 1959, North Vietnam committed to the overthrow and annexation of the South and began expanding the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The National Liberation Front (NLF) was organized in 1960 to provide Hanoi with administrative control over the Viet Cong forces in South Vietnam. Ho remained an important figure within the North and motivated the nation to continue the fight against the South and their American allies, though his health declined throughout the 1960s. In 1965, his condition began to seriously deteriorate, and on September 2, 1969, Ho Chi Minh died in Hanoi.